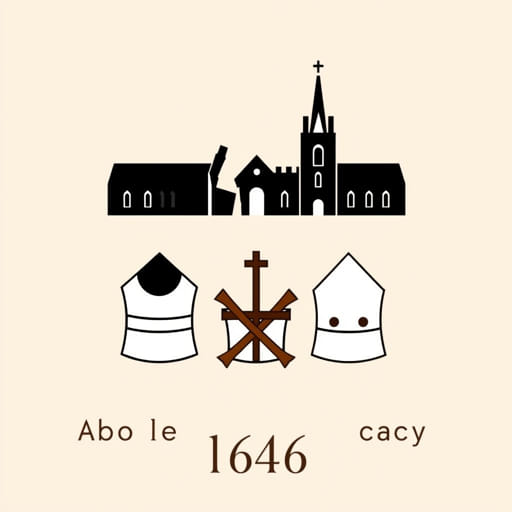

In the turbulent mid-17th century, religious authority and governance were deeply intertwined with political power in England. The abolition of episcopacy in 1646 marked a decisive moment in this conflict, as the structure of church leadership through bishops known as episcopacy was officially dismantled by Parliament. This action came amid the English Civil War, during which questions of royal power, religious authority, and national identity were intensely debated. The 1646 ordinance did not emerge in isolation but was a result of years of tension between royalists, who supported the king and the episcopal system, and Parliamentarians, many of whom favored Presbyterian or other non-hierarchical religious structures.

Background of Episcopacy in England

Episcopacy refers to a form of church governance where bishops hold authority over religious affairs, dioceses, and clergy. This system was central to the Church of England, especially under the reigns of monarchs like Elizabeth I and James I, who saw episcopacy as a key tool for maintaining order and loyalty. Bishops were not only spiritual leaders but also political figures who often sat in the House of Lords, thus intertwining church and state affairs.

However, Puritans and other reform-minded Protestants viewed this hierarchical structure as too similar to Catholicism. They criticized bishops for enforcing religious conformity and maintaining outdated ceremonies. The demand for reform of the episcopal system gained momentum, particularly among the Parliamentarian faction, which increasingly associated episcopacy with tyranny and royal absolutism.

The Lead-Up to Abolition

During the early 1640s, as tensions between King Charles I and Parliament escalated, control over the church became a major battleground. The king staunchly defended the episcopal system, seeing it as divinely ordained and integral to his rule. Parliament, increasingly influenced by Puritan sentiment and Presbyterian ideology, pushed back.

In 1641, Parliament passed theRoot and Branch Petition, which demanded the complete eradication of episcopacy. Though it was not immediately acted upon, this petition demonstrated the depth of public support for reform. Over the next few years, bishops were excluded from Parliament, and some were imprisoned or forced to flee. The outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 further polarized the issue, with Royalists defending bishops and Parliamentarians calling for their removal.

The 1646 Ordinance

Formal Abolition of Episcopacy

On October 9, 1646, Parliament passed the ordinance that formally abolished episcopacy in England and Wales. This landmark decision declared that bishops and archbishops, along with all cathedral chapters and offices associated with them, would be dissolved. Their lands and revenues were confiscated and repurposed to fund the parliamentary war effort and support clergy under the new system.

The 1646 ordinance was a culmination of years of religious and political pressure. It effectively ended the authority of bishops, replacing them with a more decentralized and Presbyterian-style church governance. Although not all parts of the new structure were fully implemented, the act signaled a significant transformation in the relationship between the church and the state.

Contents and Implications of the Ordinance

The ordinance had several key components:

- Elimination of episcopal sees and titles

- Seizure of church lands and properties associated with bishops

- Termination of all legal and religious privileges formerly held by bishops

- Promotion of a new church governance model based on local assemblies and synods

These measures not only aimed to transform the religious landscape but also to weaken royalist power. By dismantling episcopacy, Parliament hoped to establish a more egalitarian and accountable church that would align with their political vision.

Religious and Political Goals

The abolition of episcopacy was not purely a religious matter; it had strong political undertones. Many Parliamentarians believed that bishops had supported tyranny by aligning too closely with the monarchy. By removing them, reformers sought to create a more democratic church structure that reflected the political changes they were enacting in the state.

Moreover, replacing bishops with assemblies allowed for a broader base of participation among ministers and lay leaders. This change was seen as empowering local congregations and aligning with the broader Protestant ethos of reform, scripture, and individual conscience. For Scottish Presbyterians, who had allied with the Parliamentarians during the war, the abolition was a victory for their vision of church governance.

Resistance and Repercussions

Despite its legal status, the abolition of episcopacy faced resistance in many areas. In parts of England, particularly where Anglican traditions were strong, local populations remained loyal to the episcopal structure. Some clergy refused to accept the new system, leading to conflicts within parishes and regions.

Furthermore, the move alienated certain moderates who had supported limited church reform but did not favor a total overhaul. The more radical elements of Parliament, especially the Independents, clashed with Presbyterians over how far church reform should go. These divisions weakened the unified front of Parliament and foreshadowed future conflicts during the Interregnum.

The Restoration and Reversal

The abolition of episcopacy was not permanent. In 1660, following the collapse of the Protectorate and the return of Charles II to the throne, the Church of England was restored along with its episcopal hierarchy. TheAct of Uniformityin 1662 reinstated the authority of bishops and reimposed many of the old liturgical practices that had been removed during the 1640s and 1650s.

However, the episode left a lasting legacy. The events of 1646 demonstrated that ecclesiastical power was not immune to popular and political reform. The conflict over episcopacy would continue to influence debates about religious freedom, church-state relations, and the nature of authority in British society for centuries.

Legacy of the Abolition

The 1646 abolition of episcopacy remains a pivotal moment in English history. It showcased the potential for major institutional change during times of upheaval and highlighted the interconnectedness of religious and political reform. While the experiment was ultimately reversed, it paved the way for future challenges to established church authority, including the rise of Nonconformist traditions and movements advocating for religious tolerance.

In historical retrospect, the act represents both a moment of triumph for reformers and a cautionary tale about the difficulties of enforcing religious uniformity. It reveals how deeply religious identity was woven into the fabric of political power, and how efforts to reshape one often required transforming the other.

The abolition of episcopacy in 1646 was far more than a clerical reshuffle; it was a profound assertion of parliamentary authority over church structure and doctrine. Rooted in years of ideological struggle, the decision reflected broader efforts to reshape England’s political and religious future. Though short-lived, it left an enduring impact on the country’s ecclesiastical history and remains a key chapter in the story of the English Civil War and the evolution of British democracy.