In the aftermath of the American Civil War, the Southern economy faced a radical transformation. Former slaves were now free, and plantation owners no longer had access to forced labor. As a result, a system known as sharecropping emerged as a dominant method of agricultural labor. While it promised independence and self-sufficiency for freedmen, in reality, it often led to a relentless cycle of poverty. The sharecropper cycle of poverty became a defining feature of the post-war South, trapping generations in economic hardship and social inequality.

Origins of Sharecropping in the Post-Civil War South

Following the abolition of slavery in 1865, the Southern agricultural economy was in disarray. Landowners needed laborers to cultivate cotton and other crops, but many formerly enslaved African Americans had no land, money, or tools. Sharecropping was developed as a compromise: landowners would provide land, seed, and tools, while the laborer would contribute the work. At harvest time, the crops were divided typically, the landowner would take half or more of the yield.

This arrangement was appealing to both parties on the surface. Former slaves and poor whites could farm independently without the upfront costs of land ownership, and plantation owners could continue profiting from agricultural production. However, the power dynamics heavily favored the landowners.

How the Sharecropper Cycle Worked

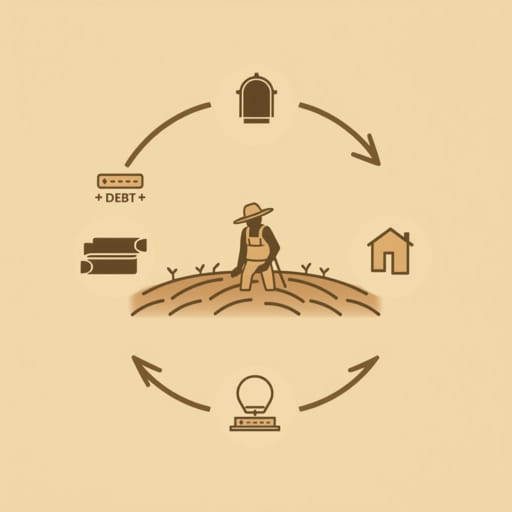

Though sharecropping appeared to offer autonomy, it created an exploitative structure. The cycle began with the sharecropper entering into a contract with a landowner. Often, these contracts were deliberately vague or filled with legal jargon, placing the sharecropper at a disadvantage. The sharecropper would then receive supplies on credit plows, seeds, food, clothing from the landowner or a local merchant, with promises to repay the debt after the harvest.

When harvest time came, the landowner controlled the sale of the crop and its valuation. Expenses were subtracted from the sharecropper’s earnings, but because the prices were manipulated or the crop yield was poor, the sharecropper often ended up in debt. This debt carried over to the next season, binding the laborer to the land indefinitely.

Structural Factors that Perpetuated Poverty

Several key factors kept sharecroppers trapped in poverty:

- Lack of Education: Most sharecroppers had limited or no access to education, making it difficult to challenge unfair contracts or manage finances effectively.

- Legal Manipulation: Southern laws were often written and enforced to protect landowners. Courts favored white landowners, and illiterate sharecroppers had little legal recourse.

- Debt Peonage: Sharecroppers were frequently caught in a web of debt that legally bound them to their landowners, preventing them from moving or seeking better opportunities.

- Fluctuating Crop Prices: Prices for crops like cotton were unstable, and a bad harvest or market downturn could plunge a family further into debt.

- Discriminatory Practices: Black sharecroppers were systematically denied fair wages and often subjected to intimidation or violence if they resisted the system.

The Role of Race and Discrimination

Although sharecropping affected both Black and white farmers, African Americans bore the brunt of the exploitation. Former slaves hoped that land ownership would be a path to true freedom, but systemic racism prevented them from accessing land, credit, and legal protection. ‘Forty acres and a mule,’ a promise made during Reconstruction, was never fulfilled for most freedmen.

Instead, Black sharecroppers remained economically dependent on white landowners who continued to dominate Southern society. White supremacist laws and organizations, such as the Black Codes and Ku Klux Klan, further suppressed Black autonomy and reinforced racial hierarchies. The sharecropping system thus became another form of control, reminiscent of slavery in its outcomes if not in its form.

Generational Impact and the Inheritance of Poverty

The economic effects of sharecropping were not limited to individual laborers. Because debts carried over year after year, families became locked into the system. Children of sharecroppers often had to work in the fields from a young age, missing out on education and continuing the cycle of low literacy and poverty.

Even when opportunities arose to leave the land, many sharecroppers lacked the resources to do so. By the early 20th century, mechanization and industrial jobs in the North led to the Great Migration, where millions of African Americans left the South. However, for those who remained, sharecropping continued to dominate rural life until well into the mid-20th century.

Economic Alternatives and Efforts at Reform

Several attempts were made to break the cycle of poverty. New Deal programs in the 1930s offered subsidies and reforms through agencies like the Agricultural Adjustment Administration. Unfortunately, many of these benefits were distributed through local white authorities who excluded Black farmers.

Later, the Civil Rights Movement sought to address economic as well as legal injustices. Organizations like the NAACP and SNCC fought for voting rights, equal pay, and land reform. These movements brought national attention to the plight of Southern sharecroppers, but by then, the system had already caused irreversible generational damage.

Legacy of the Sharecropper System

The legacy of the sharecropper cycle of poverty can still be felt today. Many descendants of sharecroppers live in economically depressed areas of the rural South. The wealth gap between Black and white Americans has roots in these historical systems of exploitation.

Additionally, the environmental consequences of monoculture farming, particularly cotton, have left some regions depleted and infertile. The failure to provide land and education to freedmen after the Civil War created a cycle not only of poverty but of systemic inequality.

A System That Shaped a Region

Sharecropping was more than just an economic arrangement it was a system that shaped Southern society, race relations, and the structure of rural life for nearly a century. What began as a post-war compromise evolved into a mechanism of control that stifled opportunity, reinforced racial inequality, and embedded poverty deep into the roots of American history. Understanding the sharecropper cycle of poverty is essential to comprehending both the failures of Reconstruction and the enduring challenges of economic justice in the United States.